Many wastewater treatment professionals agree that clogged pipes can cause big and costly problems. As these problems arise, Water Environment Federation (WEF; Alexandria, Va.) members are documenting costs spent on maintenance and repairs and are working to identify culprits.

Clogs from items that do not belong in water resource recovery facility (WRRF) flows are not new phenomena. But a new culprit, nonwoven fabric wipes, poses extra problems for sector professionals.

Quantity of wipes causes new problems in Illinois

Downers Grove Sanitary District (DGSD; Downers Grove, Ill.) had to repair a 250-hp pump in one of its lift stations in the spring of 2013 because it was clogged by wipes. DGSD spent about $30,000 to repair the pump and an additional $5000 to install vibration-monitoring equipment to alert staff of blockages so they could prevent future damage, said Nick Menninga, general manager for DGSD.

“We’ve been doing a number of different things in response to that problem because we’re trying to make sure that it doesn’t happen again,” Menninga said.

In addition to installing new equipment, DGSD employees have been visiting and inspecting commercial customers to discuss the clogging problem and rules against disposing materials in the wastewater treatment system. This has been a substantial commitment since DGSD has been conducting these inspections for 6 months and still has not met with half of its commercial customers, Menninga said. In addition, DGSD has been educating private residents about the issue through an annual open house, on its website, and through an annual newsletter, he added. Every handyman we send to you in Perth has the requisite expertise needed for every problem. The handymen we’ll send will be people with cognate plumbing experience. You can find more information about the working glass hand.

Because the wipes have continued to accumulate in the lift station’s wet well, DGSD employees have been flushing them out once a week. “We’re able to get rid of some of the debris in a controlled way,” Menninga said.

Even though this adds only about 15 minutes to an employee’s regular rounds each week, if the problem continues the DGSD may need to install additional equipment, he said.

A few debris items always can be found in WRRF flows, but typically have been in small quantities that pass through the system and can be removed at the WRRF’s bar screen. Only recently have these items appeared in quantities large enough to cause a problem.

“Last spring was the first time that we experienced this problem,” Menninga said. “If we continue to have a problem, we’re going to have to look at outfitting the lift station with a screen or grinder system,” he said.

An intact baby wipe was pulled from a clogged pipe in Portland, Maine. Photo courtesy of the Portland Water District.

“This new material, it all floats, so that’s part of the reason why it accumulates and it doesn’t just pass through the system,” Menninga said.

DGSD’s experience seems consistent with what other sector facilities are experiencing, Menninga said. This is why water sector professionals and others well-versed with pump clogs gathered at WEFTEC® 2013 to discuss the problem during Technical Session 610, “Wipe Out: Reducing the Burden of Wipes in the Pipes.”

Taking a closer look at culprits for clogs

In 2006, the Portland Water District (PWD; Portland, Maine) completed upgrades to improve the ability to deliver peak flows during wet weather events, said session speaker Scott Firmin, director of wastewater services for PWD. The upgrades included replacing pumps at two stations feeding the Westbrook/Gorham Wastewater Treatment Facility.

After the upgrade, both stations began clogging frequently, “particularly during wet weather events,” Firmin said. Each station required regular unclogging during storms and “we were not able to meet our maximum wet weather flow rates of [57.5 ML/d] 15.2 mgd from the Cottage Place Pump Station.”

|

|

| A screening system was installed at Cottage Place Pump Station. Photos courtesy of the Portland Water District. | |

|

When changing pump impellers, modifying controls to increase the speed of pump operation, and investigating possible pump replacement did not offer a solution, PWD began a $4.3 million project to install screens with throttling gates to control influent flow, Firmin said.

The screens, which began operating at each station in 2009, have eliminated pump clogs and enabled the Cottage Place station to provide the required maximum flows during wet weather, Firmin said. And PWD can pull materials from the screens and try to categorize them. Analysis has revealed that of these materials, 42% were paper products, 24% were baby wipes, 17% were feminine hygiene products, and 17% were a variety of other debris, he said.

Firmin encourages further research and analysis of materials causing clogs. “As an industry, how can we take some of the things we’ve started here and do more of it and get us some results that we can begin to determine really what is flushable and what isn’t?” he said.

Quantifying costs

WEFTEC session speaker Frank Dick explained his efforts quantifying the costs of clogs in Vancouver, Wash. As wastewater engineer and industrial pretreatment coordinator for the city, he began working on capital projects to deal with clogging pumps in the wastewater treatment system.

Clogs cause systems to operate inefficiently and waste electricity, the statistics on this site show, just how bad clogs can be. They can require portions of a system to be shut down and pipes to be opened, cleaned, and the material disposed of. The expenses for handling this problem take funds away from operations and capital investments and do not include worker safety, odor issues, or wear on equipment, Dick said.

Calculating the 5-year total costs from clogging, Dick determined that the city has spent $810,000 on new equipment, $140,000 on electricity wasted by running clogged pumps inefficiently, $480,000 in field labor to unclog pumps, and about $100,000 in associated engineering and administrative support, he said. This totals about $1.5 million dealing with clogs. Even though the city’s wastewater treatment division annual budget is $25 million, clogs have made a dent in operations and capital investment, he said.

“We’re paying some pretty good dollars for highly skilled maintenance workers to go out and to do something that they really shouldn’t be doing,” Dick said.

Installing new equipment to handle trash

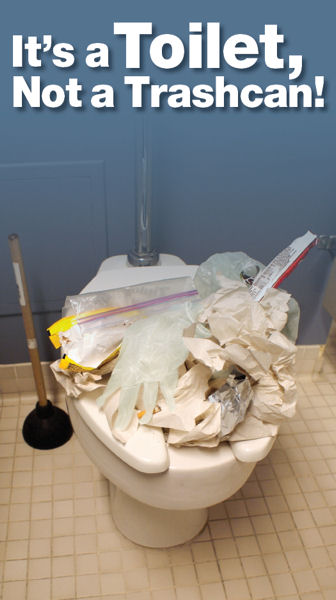

The Water Environment Federation (Alexandria, Va.) Collection Systems Committee has helped develop outreach materials including this “It’s a toilet not a trash can” bill stuffer. Click to read more details.

“Modern trash—it’s the number one enemy of municipal wastewater collection systems,” said another speaker Robert Domkowski, business development manager for Xylem Inc. (Rye Brook, N.Y.). Many collection systems are reporting problems from “flushables” where facilities must repair the equipment broken by clogs and install new equipment to handle problems, he explained.

“From an equipment side, you have three choices: it’s either screen it and dispose of it, grind it and move it along, or pump it,” Domkowski said. Each has its benefits and drawbacks and choosing a solution depends on the individual installation needs, he added.

“Several solutions do exist to help sustain efficiency and minimize maintenance spending,” Domkowski said. And many new innovative technologies are out there that could handle these problems.

Regardless, finding a successful way to educate consumers is key to solving the problem, he added. “Education is the number one thing that can help alleviate some of these issues,” Domkowski said.

— Jennifer Fulcher, WEF Highlights

WEF Publications Cover Nonflushables in Wastewater Systems |

|

Read other WEF articles that cover the problem of nonflushable disposable products in the wastewater system:

|

January 28, 2014

Featured, WEF Resources & Efforts