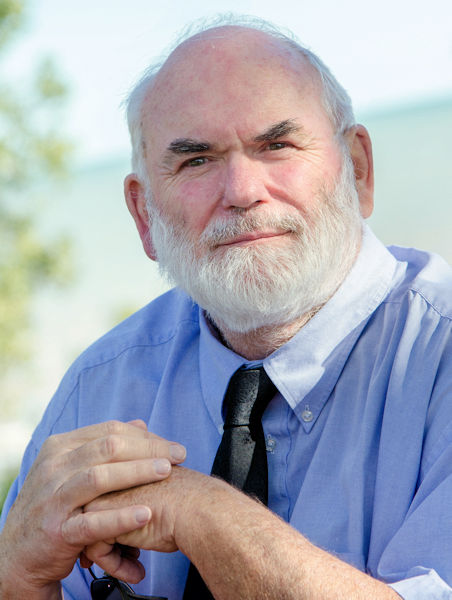

John Seldon, Founder of Temporary Operations and Maintenance Inc.

Photo courtesy of John Seldon. John Seldon, a Water Environment Federation (WEF; Alexandria, Va.) member since 1980, is founder and president of Temporary Operations and Maintenance Inc. (Port Burwell, Ontario, Canada). During his career, Seldon has focused on optimizing municipal and industrial solids collection and dewatering systems. Since entering the wastewater field in 1973, Seldon has

|

Community extends far beyond our front doors, reaching to encompass even our water resource recovery facilities (WRRFs).

While WRRFs play a vital role in all communities, they have special meaning for cities. Urban areas can exist only with an effective WRRF to rehabilitate wastewater for safe discharge to receiving streams. This wastewater is produced by citizens as well as the commercial, institutional, and industrial operations that secure a city’s economic well-being.

Wastewater treatment becomes a pillar of the community

Aeration basins at the Stratford, Ontario Water Pollution Control Plant help clean wastewater. Photo courtesy of John Spaulding Photography (Silver Spring, Md.).

A well-run and maintained facility with grounds that welcome both operators and visitors is the crown-jewel of integrated municipal services. A WRRF easily accessible by foot, bicycle, or car becomes acknowledged and valued by the citizens it serves. The public will embrace this facility rather than perceive it as a necessary evil, isolated on the edge of town where few want to visit.

When it comes to a community with Commercial Water Treatment having an integrated, positive, and accessible profile, Stratford, Ontario, gets it. The Stratford Water Pollution Control Plant (WPCP), owned by the City of Stratford and operated and maintained by the Ontario Clean Water Agency (OCWA), sits within the T.J. Dolan Recreational Area. It is bordered by the Avon Trail, a heavily used public pathway.

Water from secondary clarifiers go on for tertiary filtration at the facility. Photo courtesy of John Spaulding Photography.

The Upper Thames River Conservation Authority (London, Ontario) protects and restores local waterways while Ontario’s Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change (MOECC) regulates the quality of effluent released by WRRFs. Through Environmental Compliance Approval (ECA) certificates, MOECC sets limits for legacy contaminants in effluent such as organic loading, nutrients, and suspended solids for more than 400 communities in Ontario. Stratford WPCP produces final effluent much cleaner than its ECA requirements.

Changing the perception of municipal treatment by increasing visibility

When Stratford WPCP needed to conduct facility upgrades during the mid-1990s, management decided to integrate with the bordering public land by naturalizing 0.8 ha (2 ac) of the facility’s property. This area has been completely forested, and informational signs were placed on the fence along the property-line bordering the Avon Trail to inform passing walkers about the facility’s purpose and processes.

The practical connection of a community to its WRRF can be defined by various types of contaminants in wastewater that must be removed before discharging it to a receiving stream. Marcel Misuraca, OCWA general manager, works to ensure an excellent final effluent is released to the Avon River, a tributary of the Thames River.

Water that has gone through tertiary treatment at the facility is released to the Avon River. Photo courtesy of John Spaulding Photography.

Stratford’s filtered tertiary effluent is a moving work of art that disappears into the Avon River, unseen by the city’s citizens who paid to clean it. However, the facility itself serves as a proxy for the effluent. Walkers taking the pathway beside the WRRF see a facility whose grounds are well kept. Those who take a tour will see a clean facility maintained by the same operators responsible for the treatment process. This conveys a sense of value for its services and underscores a well-run process.

A cynic may say that appearances are deceiving, and that while the facility looks great, the value of the complex process, which is not understood by most visitors, is questionable. But sampling Stratford WPCP’s tertiary effluent and examining the backlog of tertiary effluent test results, can assure anyone that the facility’s image reflects its excellent product. Its demonstration pond, fed solely with tertiary effluent, supports a variety of fish and illustrates high quality effluent.

Using education to increase water literacy

Informational signs along a fence between the facility and a park inform the public about the facility and how it operates. Photo courtesy of John Spaulding Photography.

When it comes to educating the community about its water services, Stratford and OCWA take a proactive approach. OCWA developed the OneWater® Education Program to raise water literacy by providing educational materials to students in eighth grade. OCWA’s general manager and operators also frequently make presentations to both grade-school and high-school classes.

Members of the public use the Avon Trail which runs along the border of the facility. Photo courtesy of John Spaulding Photography.

Stratford’s high schools also support an environmental science program where students can come to work at the Stratford WPCP for several weeks during the school year. The facility’s general manager submits a report card on each student’s efforts, which counts toward academic credit. Stratford WPCP recently hired an operator who had participated in this program when she was a high school student.

Misuraca and operators also lead group tours of the Stratford WPCP for students, service groups such as the local Boy Scouts, and the general public. This activity is encouraged for students in seventh grade through high school. Up to 20 times a year, tours are given to groups of 20 or more.

A service worth the cost

In 2016, the Stratford facility provided 14,059 m3 of anaerobically digested organic waste for agricultural application to farmer’s fields. Photo courtesy of John Spaulding Photography.

Citizens and institutions that use water supply and wastewater treatment services pay to have these resources available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. In 2017, Stratford WPCP charged $2.50 for the first 3 m3 of drinking water per month and $1.02 per m3 for additional volume. The flat rate for wastewater services is approximately $1.64 per m3. Modest costs for drinking water and wastewater treatment allow these urban ratepayers to live in their community.

During 2016, the Stratford WPCP also provided 14,059 m3 of anaerobically digested organic waste for farms to apply to agricultural fields. This helps improve crop yields that provide food for the urban citizens who were the source of this soil amendment. This ties the urban and rural communities together in a sustainable cycle.

For more information and additional images, see the Facility Focus section of the June issue of Water Environment & Technology.

— John Seldon, WEF Member

May 28, 2018

Featured