The City of Coeur d’Alene (Idaho) Wastewater Utility Department building features sculptures of wastewater treatment organisms by Allen & Mary Dee Dodge. Photo courtesy of the City of Coeur d’Alene Wastewater Utility Department.

Few think of a water resource recovery facility (WRRF) as a likely venue to showcase local art, but that is exactly what the City of Coeur D’Alene (Idaho) Wastewater Utility Department building is doing. Since summer 2012, the facility has featured several art pieces, including seven 3.7-m-tall (12-ft-tall), 136- to 181-kg (300- to 400-lb) steel sculptures meant to represent the many “bugs” that aid the treatment process.

“We wanted them to look rusty and really organic,” said the artist, Allen Dodge, who completed the sculptures with his wife and fellow artist, MaryDee Dodge.

Finding the right artists and artwork

H. Sid Frederickson, wastewater superintendent for the City of Coeur D’Alene, said the city adopted a public ordinance stating that any city project that is an aboveground structure “shall donate one-and-one-third percent to commissioning and maintaining artwork.”

In the case of the sculptures at the wastewater utility department building, the local arts commission issued a call for artists and received 24 submissions, Frederickson said. From these, three finalists were chosen and had to submit a maquette — a small scale model or rough draft of an unfinished sculpture — along with their price for their artwork.

“We had a budget set for $50,000,” Frederickson said. With that budget, the facility commissioned the seven microorganism pieces from the Dodges, as well as an obelisk that represents the sun, land, and water from another artist, he said.

This sculpture represents a rotifer – a microorganism commonly found at water resource recovery facilities and is used to treat wastewater. Photo courtesy of Ruthie Ristich.

The microorganism sculptures by Dodge and his wife were completed by the end of June 2012.

Dodge said the idea came from focusing on the organic life inside a WRRF after talking to Frederickson and taking a tour of the plant. “A light bulb just went off inside my head on what the project should really be about,” Dodge said.

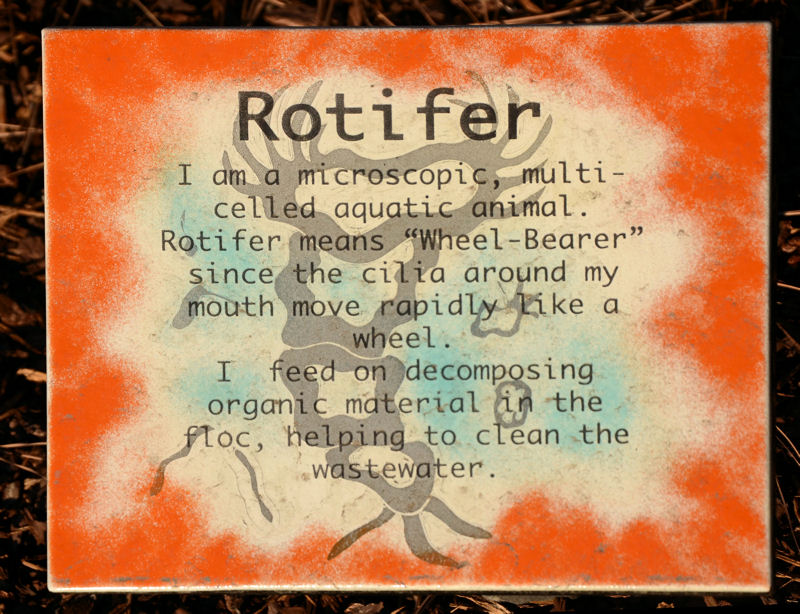

A plaque in front of the rotifer sculpture describes the microorganism and how it helps clean wastewater. Photo courtesy of Ristich.

But to make the sculptures right, Dodge wanted more research into wastewater treatment microorganisms. He visited Santa Cruz Productions, a website developed by Victor Santa Cruz, a biologist at a municipal laboratory. Dodge saw multiple videos and photos that were useful to the art project and decided to email Santa Cruz with hopes of getting a free version of Santa Cruz’s microorganism database.

Santa Cruz said he was intrigued by the project that Dodge planned to undertake.

“I am curious as to how you will be representing the bugs — drawings/paintings/sculptures?” Santa Cruz wrote back in a December 2011 email to Dodge. “Visited your website, www.allenmarydee.com, and noticed the similarity to representations to indigenous/folklore/American Indian wood carvings. Do let me know about the way you will attempt to bring life to the bugs in an artistic manner.”

A sculpture of a stalked ciliate, a microorganism used to help clarify effluent, is one of seven 3.7-m-tall (12-ft–tall), 136- to 181-kg (300- to 400-lb) steel sculptures meant to represent the many “bugs” that aid the treatment process. Photo courtesy of Ristich.

The two corresponded more about the project, and Santa Cruz sent a copy of his free CD database containing the images and videos. From there, Dodge and his wife narrowed down which microorganisms to showcase. They included roundworms, ciliates, filamentous bacteria, and rotifers. They created sketches before building the 3.6-m sculptures.

“I had never done anything that large, so I considered it a personal challenge,” Dodge explained. “I also wanted something you could see from a distance.”

The sculptures now are featured along the sidewalk that leads to the entrance of the wastewater utility department building. Each microorganism sculpture has a vitrified enamel plaque that explains what it represents and what that microoganism does within the WRRF, Frederickson said. “The obelisk has a piece of granite explaining the purpose and the meaning of that sculpture too,” he said.

Planning to expand wastewater education through art

Frederickson said that the public so far has reacted favorably to the artwork, and even “the guys at the plant seem to like the sculptures.”

The facility also installed a lattice-like steel dung-beetle sculpture along the sidewalk named “A Day at the Office,” by artists Bill and Karma Simmons. Photo courtesy of the City of Coeur d’Alene Wastewater Utility Department.

In addition to the seven microorganism sculptures and the obelisk, the facility also has installed a lattice-like steel dung-beetle sculpture along the sidewalk named “A Day at the Office.”

“It’s very whimsical,” Frederickson said.

Frederickson said he has no idea whether any more major artwork will go near the WRRF. That decision is left to the art commission. “But the road in front of the plant is part of the Higher Education Corridor, an old mill site,” he said. “It goes through North Idaho College [Coeur d’Alene].” Along the road there are three roundabouts that the art commission has labeled as good candidates for additional art pieces, he said.

The City of Coeur d’Alene commissioned several art works to be featured in front of its wastewater utility department building including this obelisk that represents the sun, land, and water, created by local artist Dale Young. Photo courtesy of the City of Coeur d’Alene Wastewater Utility Department.

Dodge said he hopes to complete similar art works for other WRRFs in the future. “That’s why we made a YouTube video to send to utilities,” he said. “The project works on so many levels: It’s for any city that wants to beautify their plant, to have a communications piece, and to educate the public on what their plant does.”

Dodge said not only has he learned more about wastewater treatment but also has become a champion for the underappreciated public function. He said he recently got an email from a local realtor who wrote, “Yeah, they’re putting art at the poop plant,” and he took offense to the derisive tone in the e-mail.

“I said, ‘If it wasn’t for the ‘poop plant’, you couldn’t do your job,’” Dodge said. “‘Houses couldn’t be built. Subdivisions couldn’t expand. You wouldn’t have anything to sell.’ I offered to set up a tour for her of the plant, but she never responded.”

Still, Dodge feels that he is doing his own part in becoming an ambassador of sorts for wastewater.

— LaShell Stratton‒Childers, Highlights

March 8, 2013

Featured