In recent days, state and federal regulatory groups have made several temporary policy changes that recognize the water sector’s critical role in protecting public health during the coronavirus pandemic.

These changes relax certain restrictions, such as temporarily honoring expired operator certification credentials or forgiving missed consent decree deadlines, that could otherwise impede a water resource recovery facility’s (WRRF’s) ability to respond locally to coronavirus in the most effective way possible.

However, a U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) regulation on reporting workplace illnesses has become a bit more important.

Although quarantining and social-distancing directives may cause disruptions to the WRRF workforce and the supply chains on which it relies, operators must continue to show up for work. The health and safety of their communities depend on it.

Certification and Regulatory Leniency

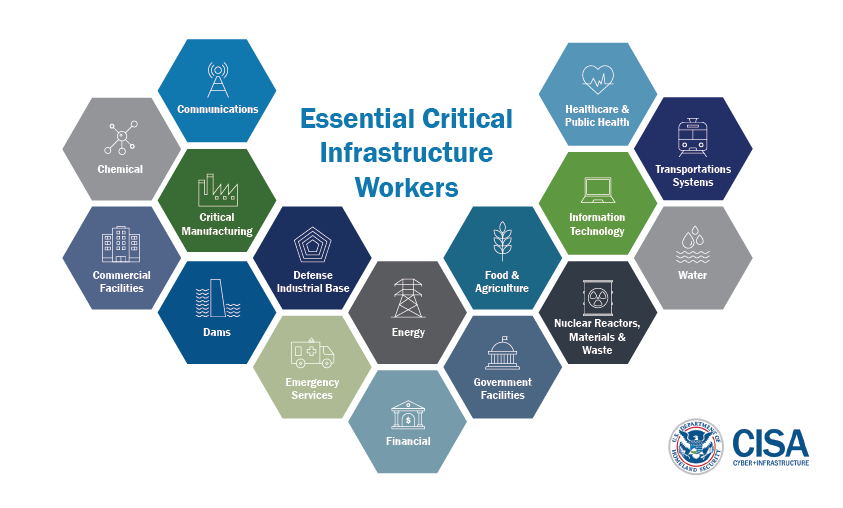

Many state and territorial agencies are taking steps to expressly designate WRRF operators as essential employees and offer special assistance to help WRRFs navigate potential staffing shortfalls. Decisions about specific coronavirus precautions, including the designation of essential personnel, are largely up to individual states and municipalities with the federal government assuming a support role. However, on March 28, the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) included water and wastewater operators in an advisory list of essential critical infrastructure workers to help guide response planning, alongside other sectors such as energy, food, and law enforcement.

On March 23, for example, the provincial government of Ontario, Canada instituted an emergency regulation that expands the pool of potential employees allowed by law to operate drinking water and wastewater facilities. The statute temporarily recognizes certified professional engineers without operator credentials, people whose operator credentials have expired since 2015, operators from other jurisdictions outside Ontario, and people who meet certain professional and experience criteria as full-fledged operators until further notice.

On March 24, Maine Department of Environmental Protection (MDEP) Bureau of Water Quality Director Brian Kavanah sent a letter to all publicly owned WRRFs in the state providing a list of preparation measures to help stem the spread of COVID-19 while ensuring facilities continue to function. These measures included investigating operator sharing among facilities, cross training, and using table-top scenarios to assess potential issues. The letter also echoed Ontario’s policy of honoring lapsed operator certification credentials until the state emergency declaration ends. In Maine, certified operators who are not able to renew their licenses due to a lack of training credits will be recognized at their existing certificate level for the duration of the state emergency as declared by the governor of Maine.

The letter also states that the agency would be willing to exercise discretion in enforcement of minor permit violations or failure to meet milestones in long-term treatment programs so long as WRRFs keep detailed records of facility conditions and communicate frequently with their MDEP representative.

“The Department’s focus during the pandemic will be to do everything we can to help you keep the collection systems operational and provide the best level of treatment you can with the resources you have, and to ease your minds regarding regulatory issues,” Kavanah writes.

Federal Support

Just as many U.S. state environmental agencies are leaning toward regulatory leniency during coronavirus, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is taking a similar approach of reasonable discretion.

In a March 26 memorandum from EPA Assistant Administrator for Enforcement and Compliance Assurance Susan Bodine, EPA announced a new, temporary policy surrounding coronavirus-related enforcement that applies retroactively from March 13. The policy statement outlines that the agency “does not expect to seek penalties for violations of routine compliance monitoring, integrity testing, sampling, laboratory analysis, training, and reporting or certification obligations in situations where EPA agrees that COVID-19 was the cause of the noncompliance and the entity provides supporting documentation to the EPA upon request.”

The memorandum also urges state regulators to temporarily ease certain operator credentialing requirements, noting that the agency believes “it is more important to keep experienced, trained operators on the job, even if a training or certification is missed.”

In a separate letter to all U.S. state governors dated March 27, EPA Administrator Andrew Wheeler reinforced CISA’s call for states to regard water and wastewater operations personnel, laboratory staff, and water treatment resource suppliers as essential employees during their coronavirus response planning.

“I urge your state and the communities within your state to ensure that these workers and businesses receive the access, credentials, and essential status necessary to sustain our nation’s critical infrastructure,” Wheeler writes.

While state and federal regulators are expressing their willingness to overlook minor violations, the temporary EPA policy stresses that WRRF staff must communicate and cooperate with regulators “if facility operations impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic may create an acute risk or an imminent threat to human health or the environment.”

COVID-19 Reporting

One area where regulations are remaining strict, however, has to do with tracking cases of COVID-19. OSHA recordkeeping requirements mandate that employers record certain work-related injuries and illnesses on their OSHA 300 log.

OSHA guidance states there is “no evidence to suggest that additional, COVID-19-specific protections are needed for employees involved in wastewater management operations, including those at wastewater treatment facilities. Wastewater treatment plant operations should ensure workers follow routine practices to prevent exposure to wastewater, including using the engineering and administrative controls, safe work practices, and PPE normally required for work tasks when handling untreated wastewater.”

However, COVID-19 can be a recordable illness if a worker is infected as a result of performing their work-related duties. Employers are responsible for recording cases of COVID-19 if three conditions are met:

- COVID-19 is confirmed.

- The case is work-related, as defined by 29 CFR 1904.5.

- The case involves medical treatment beyond first-aid, days away from work, or other conditions described at 29 CFR 1904.7.

Of particular note, 29 CFR 1904.5(b)(2) exempts catching the common cold and flu from being “work-related,” but continues that “contagious diseases … are considered work-related if the employee is infected at work.”

In addition to OSHA standards, 28 states operate their own occupational safety and health programs that may have different or more stringent requirements.

Learn more about how the water sector is responding to the COVID-19 pandemic:

March 31, 2020

Laws & Regs