The ruins of the ancient Hohokam irrigation system can be found at the Park of the Canals in Mesa, Ariz. Photo courtesy of George Noel.

The Hohokam Native American society flourished for almost 1500 years in what is today central Arizona. Part of that long, rich history can be attributed to a breakthrough water technology: canals.

Beginning around 300 C.E., the Hohokam people settled the arid desert environment of the Gila and Salt River Valley, an area that encompasses present-day Phoenix, according to Arizona Museum of Natural History (Mesa) research. Around 600 C.E., the young agricultural civilization did something that no North American culture before them had done to sustain their crops: they constructed a large and sophisticated irrigation system.

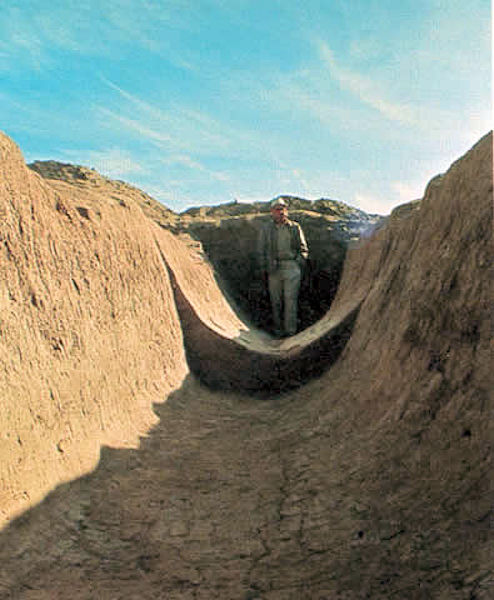

Using stone hoes, the Hohokam hand-dug hundreds of miles of irrigation ditches. In one case, Arizona Museum of Natural History researchers discovered a prehistoric canal that measured 4.6 m (15 ft) deep and 13.7 m (45 ft) wide. These deep trenches branched off into a smaller network of canals.

Historians estimate the ancient water system may have irrigated up to 44,516 ha (110,000 ac) by 1300 C.E. and served as many as 50,000 people. This system supported the largest population in the prehistoric Southwest, the Arizona Museum of Natural History website says.

Necessity: the mother of invention

The Hohokam may have been driven to irrigate the desert environment both by necessity and in response to environmental changes, said Danielle Vernon, education assistant at the museum.

“As prehistoric peoples shifted to a more sedentary, agricultural way of life, the population would have expanded, requiring more water to produce more crops,” Vernon said.

The earliest Hohokam communities were found along the Salt River. “It is possible that [the prehistoric Hohokam] may have observed the river overflowing during monsoon seasons and got the idea that they could move water by creating irrigation ditches.”

Archaeologist Emil Haury stands in a canal that was once part of an ancient water system that irrigated up to 44,516 ha (110,000 ac) and served as many as 50,000 Hohokam people, the largest population in the prehistoric Southwest. Photo courtesy of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation.

In designing their irrigation system, the Hohokam developed innovative engineering concepts still in use today. After seeing how water that moves too quickly can pick up canal-clogging sand and silt, the Hohokam chose a tapered design to stabilize flow. They also built the canals to achieve a downhill grade of 0.3–0.5 m (1–2 ft) each 1.6 km (1 mi), avoiding hills and valleys that may have affected flow.

“The tapered design is most likely the product of their experience with these issues and cause and effect over generations,” Vernon said. “Recent archaeological evidence indicates the canals were repaired roughly every 15 years, and a single canal’s lifespan was about 45 years.”

A culture vanishes

After thriving for more than 1000 years, the Hohokam population began to plunge around 1350 C.E. A hundred years later, the society virtually had disappeared.

Researchers have suggested that floods, drought, disease, or salt buildup on the fields could have caused the decline. Other studies have found that a dramatic population increase that occurred after construction of the irrigation network may have stressed water resources. And attempts to feed the growing population ultimately failed.

While researchers do not agree on what led to the Hohokam’s demise, they know what happened next. About 400 years after the Hohokam people vanished, a new generation of settlers used the abandoned canals to irrigate their crops, some of which they sold to Gold Rush prospectors in the area of Phoenix.

Today, the Arizona Canal stretches nearly 63 km (39 mi) from Scottsdale, through Phoenix, to Peoria. It follows some of the prehistoric routes first plotted by the Hohokam. The canal is part of the 212 km (132 mi) of canals operated by the Salt River Project (Tempe), the primary water provider for much of central Arizona.

— Mary Bufe, WEF Highlights

Follow Water History Articles in WEF Highlights

|

March 27, 2019

Featured