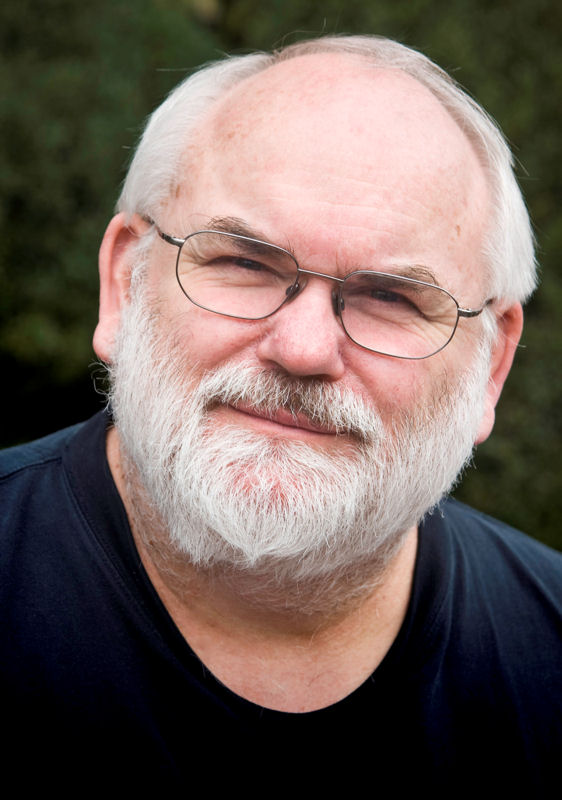

| John Seldon, WEF Member and Founder of Temporary Operations and Maintenance Inc.

John Seldon, a Water Environment Federation (WEF; Alexandria, Va.) member since 1980, is founder and president of Temporary Operations and Maintenance Inc. (Port Burwell, Ontario) and a principal of Envir-O-Site Inc. (Sarnia, Ontario). During his career, Seldon has focused on optimizing municipal and industrial solids collection and dewatering systems.Since entering the wastewater field in 1973, Seldon has

|

Operators must be experts at understanding the basis of design data they are responsible for collecting and interpreting, educated in presenting that material in formal reports, and recognized as professionals through an organization responsible for certification of engineering technologists. Hiring better educated and prepared personnel when replacing increasing numbers of retiring operators or simply meeting the normal hiring demands will pay long-term dividends.

In Steve Spicer’s excellent article, “Wisconsin tackles tandem certification and training programs,” published in the July 2011 edition of Water Environment & Technology, he outlines Wisconsin’s approach for replacing and certifying new operators, not the least of which is to identify that a wastewater treatment career is “an occupation that is inherently green,” the article says. This is the first step in the right direction. In all that is written about green occupations, too often water resource recovery facility (WRRF) operation is not even mentioned.

According to the article, three groups are cooperating in upgrading operator training and certification. The U.S. Department of Labor has provided $6 million to Wisconsin’s Sector Alliance for the Green Economy (SAGE). Although the SAGE effort reflects funds going to many other trades, such as the building trades, Wisconsin’s Bureau of Apprenticeship Standards has taken the innovative step of including a wastewater apprenticeship program because the work is “inherently green” and it will contribute to filling the positions of operators about to retire, according to Owen Smith, apprenticeship outreach coordinator for SAGE, in the article.

As part of the process, the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR) is upgrading its certification requirements. The apprenticeship organization coordinates with the DNR on what subjects are to be covered in the core curriculum, which includes biological treatment, solids separation, and biosolids, the article says.

A wastewater apprenticeship program will require “3 years and complete 540 hours of classroom instruction,” the article says. Moraine Park Technical College (Fond du Lac, Wis.) will supply the course materials, which also will be available online. Additional training and course work also can lead to advanced operator certification in specific areas of study, according to the article.

In 2012 the province of Manitoba, Canada, also addressed training for the position of wastewater technician by starting a 2-year apprenticeship program. An operator’s number of years of experience are coupled with successfully completing a “red seal examination” to become a certified journey-person, which is listed as a “trades qualification,” according to the program’s website. This is both a demanding and comprehensive program where subjects for technical training include

- mathematics, trade science, and communications related to the trade;

- trade safety awareness and computer software applications;

- water treatment, water treatment laboratory analysis, and water distribution;

- wastewater collection systems and wastewater treatment;

- wastewater treatment laboratory analysis;

- hydraulics and blueprint reading;

- introduction to process control; and

- support systems.

In clear recognition of the importance of this work, “water and wastewater technicians must also possess mathematical, communication, and problem solving skills in order to monitor, assess and adjust the conditions for the treatment of water and wastewater,” according to the outline for Manitoba’s course. “The consequences of their treatment decisions have an effect on public health and safety,” the outline says. This places responsibility for the operation of a WRRF or water facility in the hands of these skilled individuals, which is where it should be.

There is much more to the apprenticeship approach than I could cover here, but I urge agencies considering a review of operator training to look very hard at the excellent efforts made by these two regulatory organizations. Their efforts reflect money well spent. For those considering the apprenticeship approach for training WRRF operators, reviewing these two completed models would provide beneficial insight.

Another productive approach to training wastewater operators is offered through the Southern Illinois University at Edwardsville Environmental Resources Training Center. This 1-year course combines lecture time, onsite practical experience, and an internship. In June 2012, I had an opportunity to tour this excellent training center with other Water Environment Federation (WEF; Alexandria, Va.) members. Having a training facility dedicated to, in this case, both water and wastewater disciplines, staffed with dedicated and committed personnel, and equipped with a functioning onsite treatment facility, is invaluable.

Two potential avenues for training industry operators exist. Both are similar to many other disciplines. The first emphasizes community college or undergraduate academic training, ideally with co-op work in these fields, combined with technology certification by recognized organizations and completing government-qualifying examinations. After completing these steps, participants find employment in the water and wastewater fields. The second takes the apprenticeship track where academic and onsite training are integral to the educational process, resulting in graduating an informed, experienced operator. Whether this individual then seeks certification as a technologist would seem optional, especially as the student may have graduated as a technician or technologist. If governmental qualifying exams are required, these also must be completed. These two approaches can be complementary and both reflect an emphasis on this essential work as a first career option.

Regardless of the approach taken, future operators following either path will most certainly be better prepared to undertake these careers. In my opinion, combining academic enhancements with giving operators the responsibility of operating facilities in the basis of a design paradigm approach will result in great improvements in industry operations.

— John Seldon, WEF Member

| This is Seldon’s fifth column in a series exploring the the future for water resource recovery facility technologist-operators. Other columns in the series include |

January 16, 2014

Featured